Play Space Utopia: Reimagining Dementia Care Through Architectural Play

Challenging Conventions in Dementia Architecture

At a time when the world’s elderly population is expanding rapidly, few have dared to truly upend the conventional blueprint for dementia care spaces. Jacqueline Lau, a recent Master’s graduate from the Manchester School of Architecture, is one such innovator, breathing new life into the field with her boldly imaginative project, Play Space Utopia. Fusing rigorous academic insight with a year of hands-on practice as a Part I Architectural Assistant in Hong Kong, Lau’s design proposes an alternative vision for dementia care—one that puts “play” at the heart of healing and quality of life.

A Personal and Professional Commitment

Jacqueline’s educational pathway has been anything but ordinary. After earning her Master’s degree at one of the UK’s most respected architecture schools, she strengthened her practice in Hong Kong by working directly across all RIBA stages of design and delivery. This ground-level exposure to the realities of project implementation offered her more than just portfolio pieces; it provided a deep understanding of user needs, cultural context, and the legislative intricacies of architecture. Her yearlong immersion in the field reaffirmed her commitment to humane, inventive design, and inspired her return to the UK to push her boundaries even further.

Reframing Dementia: From Remembering to Experiencing

Conventional dementia care spaces in Hong Kong and beyond, Lau notes, are overwhelmingly curated to soothe and trigger memories—environments filled with nostalgia and routine. While these strategies are valid, they rarely address the dynamic, nuanced ways in which people with dementia interact with the present moment. For Play Space Utopia, Lau turns the brief on its head: why not create spaces that celebrate imaginative experience, rather than simply anchor identity in the past?

Drawing on dementia care home guidelines, as well as interviews and firsthand research, she pinpointed a surprising gap. “So much of the design is about helping residents remember,” she explains, “but what about creating new moments of happiness and wonder, even if they don’t recall them tomorrow? Play is a vital aspect of well-being, for any age.”

Designing with Play: Lessons from Archigram and Radical Precedents

To realize this radical ambition, Lau synthesizes theoretical influences and practical experimentation. She credits the avant-garde spirit of Archigram and the infamous Reversible Destiny Lofts by Arakawa and Madeline Gins as significant reference points. Both precedents champion unpredictable, kinetic environments—spaces that demand interaction, foster curiosity, and shun passivity.

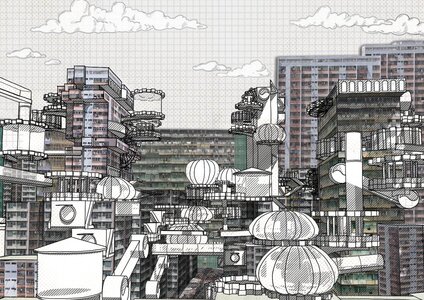

The architectural centerpiece of Play Space Utopia is an interconnected series of rotating, parasitic pods. These modular, gear-driven structures glide along carefully designed walkways, powered by motors that periodically shift their position, orientation, and even connections to one another across the masterplan. By constantly redefining user routes and rearranging the internal landscape, the playground becomes a living, breathing entity—always surprising, never predictable.

A New Kind of Playground: Movement, Light, and Cognitive Engagement

Carefully designed to exceed rather than accommodate the limitations of traditional elderly play spaces, Lau’s approach prioritizes stimulation and adaptability. The slow, deliberate rotation of each pod allows for perpetual changes in light quality, shadow, and spatial relationship. Rather than being disorienting, Lau argues, this gentle motion is intended to spark cognitive engagement: “It’s about using architecture to encourage alertness and delight through small, manageable challenges—making users partners in their own environment, no matter where they are on their cognitive journey.”

In practice, this means that residents with dementia are invited to explore a shifting environment, sometimes alone and other times with others, navigating pods that transform from sun-kissed reading nooks to cool retreat spaces within a single afternoon. Rather than being tasked with remembering, they are free to participate in play, socialization, and self-exploration at their own pace.

Escaping Routine: Creating Moments of Joy

Perhaps the most provocative aspect of Play Space Utopia is its invitation to abandon familiar care routines—just for a little while. Residents are allowed, even encouraged, to immerse themselves in the present, forging entirely new experiences rather than desperately chasing old memories. Here, the architectural language of repetition and reminiscence is replaced by one of novelty, agency, and joy.

As Lau so succinctly puts it: “At Play Space Utopia, no one has to remember anything correctly. It’s about pure experience, fun, and escape—a playground designed to honour and elevate the moment.”

Joining the Conversation: Connect with Jacqueline Lau

Play Space Utopia is more than a speculative masterplan; it is a call to action for architects, care professionals, and the wider community to reconsider what dementia care environments can and should offer. For those interested in discussing design innovation, dementia care, or play-based architecture, Jacqueline Lau welcomes engagement both professionally and personally.

She is active on LinkedIn, where she reflects on her design journey, and she regularly shares sketches, process photos, and insights on Instagram at @j_takkyl. Lau’s generosity in sharing her work makes her a standout among the next generation of architects redefining care and creativity within the built environment.

Interested in connecting or collaborating? Reach out to Jacqueline Lau on LinkedIn or follow her on Instagram @j_takkyl to learn more about her experimental, human-focused approach to architecture.

Add a comment