Sustainabowl Pavilion: Celebrating Japanese Craftsmanship with Sustainable Design

Leilou Walmsley Reimagines Small-Scale Architecture at the Welsh School of Architecture

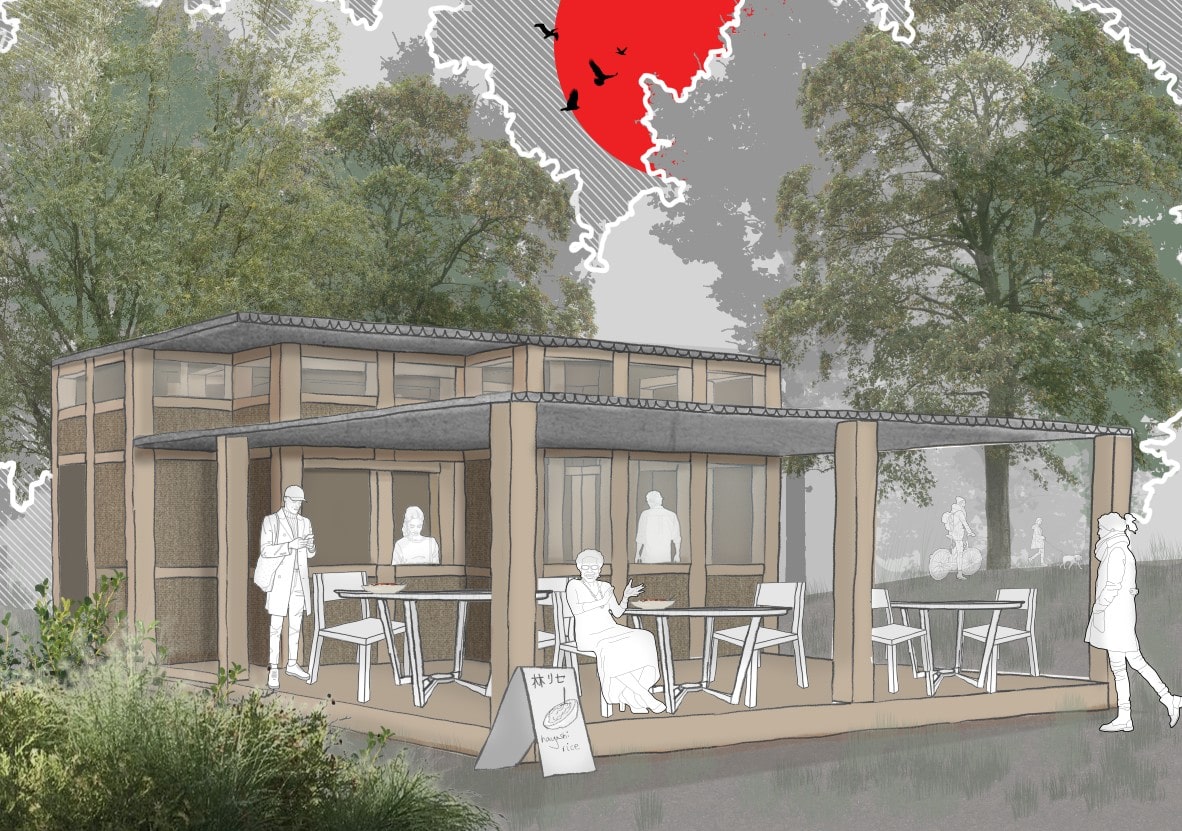

Stepping inside the Sustainabowl Pavilion, one is first greeted not by grandiosity, but by humility—a gentle homage to centuries-old Japanese building traditions, interpreted with a distinct vision for sustainability. This is the brainchild of Leilou Walmsley, a third-year undergraduate at the Welsh School of Architecture, whose fascination with modest, eco-friendly spaces laid the groundwork for a project that stands out for both its conceptual clarity and constructed integrity.

Honouring Tradition: The Miyadaiku Method Reborn

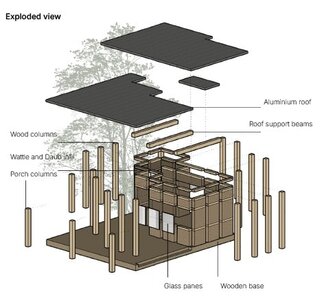

Walmsley’s Sustainabowl Pavilion is rooted in the Japanese Miyadaiku technique, a craft that traditionally eschews glue, nails, and screws in favour of precisely interlocking timber joints. By employing this revered system, Walmsley not only foregrounds a time-tested construction method but also poses an urgent question to contemporary architecture: What if impermanence and recyclability defined how we build?

The effect is a kind of tactile honesty—an embrace of material expression that encourages users to experience the pavilion as both shelter and object, much as celebrated in the work of Shigeru Ban or Kengo Kuma. The timber structure, left confidently exposed, frames the space with poised simplicity. It compels the visitor to appreciate each dovetail and mortise—connections not hidden, but highlighted as feats of craftsmanship.

Earth and Metal: Old and New in Dialogue

While the Miyadaiku skeleton embodies heritage, the pavilion’s wattle and daub wall infill forges a rural-urban link, recalling both Japanese and global vernacular traditions. Wattle and daub, a system using woven wooden slats daubed with a mixture such as clay and straw, underscores the project’s commitment to sustainability—every surface can return fully to the earth.

Above, a crisp aluminium roof introduces a contrasting, contemporary edge. Its sheen and geometry playfully riff off the tactile earthiness below, but with purpose: aluminium is famed for being infinitely recyclable, ensuring that when the pavilion’s story ends, not even its roof will languish in landfill.

This harmonious material symphony results in a structure that is, as Walmsley notes, “entirely biodegradable or recyclable.” In a climate of disposable construction and mounting waste, this is more than a design decision—it’s a philosophical statement.

Culinary Architecture: A Pavilion for Gathering and Savoring

At its heart, the Sustainabowl Pavilion is a place for food—a culinary space designed specifically to serve steaming bowls of Japanese curry. This programmed intent guides not only its spatial configurations but also its architectural language.

Much like the culinary tradition it celebrates, the pavilion achieves balance through restraint. The open floor plan facilitates movement and gathering, while the carefully controlled palette evokes the Zen-like calm of a Japanese teahouse. Subtle details nod to Japanese aesthetics: the gentle curve of the eaves, the play of filtered sunlight across timber beams, and the measured proportion of structural bays.

Walmsley’s approach is both functional and symbolic—inviting visitors to slow down, share a meal, and, perhaps, reflect on their relationship with the built environment and its lifecycle.

From Studio to Site: Learning as a Design Philosophy

It’s all the more impressive, then, that Sustainabowl emerged from Walmsley’s first year at the Welsh School of Architecture. While still an undergraduate, she grappled not only with demanding studio deadlines but with the challenge of translating traditional techniques into realisable forms. Sketches became models; models became meticulously detailed joinery studies; and finally, a pavilion took shape—at once rooted in tradition and unafraid of innovation.

Walmsley reflects: “I wanted to explore how small-scale design could be truly sustainable, not just in materials, but in how people use and dismantle it. The Miyadaiku method captivated me because it proves that temporary can also be beautiful and enduring—just in a different way.”

Her tutors cite the project as a benchmark for integrating environmental consciousness with architectural narrative. Sustainabowl has become a talking point in crits, admired not just for its visual clarity, but for its ambition—demonstrating that impactful design is possible even at a modest scale.

Building Networks: Connecting with Leilou Walmsley

For those inspired by Walmsley’s blend of craft, minimalism, and environmental responsibility, the conversation doesn’t end at the pavilion’s doorway. Leilou is open to connecting with fellow students, practitioners, and potential collaborators who share her vision for sustainable, small-scale architecture.

You can connect with Leilou Walmsley via LinkedIn to discuss her work, share ideas, or explore collaborations. Her commitment to environmentally conscious design is matched only by her enthusiasm for knowledge exchange—an approach that promises to serve her well as her career blossoms.

Leilou Walmsley’s Sustainabowl Pavilion is a timely reminder that sustainability and beauty need not be at odds. By weaving together traditional methods, biodegradable materials, and a program as convivial as the sharing of food, she offers a blueprint for young architects everywhere: start small, consider deeply, and design with the future in mind.

Add a comment